20.9.2004 #283

Re-Write 4.3.2010

by Guido Bibra

• Agatha Christie: A Portrait

• Theatrical Trailer

![]() Der Film

Der Film

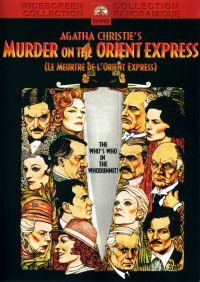

Hercule Poirot has just solved an exhausting case in Syria and is looking forward to a quiet journey from Istanbul back to Europa on the Orient-Express. But the master detective cannot escape from his profession when a murder is committed in the train. The victim is the shady Mr. Ratchett, who was unsuccessfully trying to engage the detective as a bodyguard only the day before his murder. Now Poirot faces the impossible task to find the murderer in a group of a dozen travelers before the train is freed from a snowdrift and the yugoslavian police takes over the case...

Agatha Christie is, surprisingly, not one of the most filmed authors of movie history. Even her Belgian master detective Hercule Poirot only exists in very few incarnations and only some of these were really successful. In the 1960s MGM tried to do an adaptation of The ABC Murders with Tony Randall in the title role as an answer to the Miss Marple films with Margaret Rutherford - this movie proved to be very humorous and entertaining, but not very close to the original. However Agatha Christie was absolutely not pleased with these adaptations and distanced herself from them. In the following years the author seldom allowed other movies based on her books, so that between 1965 and 1974 only two adaptations were produced, neither of which were especially good or successful.

In the beginning of the 1970s a British team of producers, Richard Goodwin and John Brabourne, were able to persuade Agatha Christie personally to allow the making of more movies based on her works. Perhaps it had something to do with the fact that Brabourne was an English Lord and a Cousin of the British Queen, but it's more probable that they had convinced the Author with their previous production, an adaptation of The Tales of Beatrix Potter, which stayed very close to the original. Agatha Christie agreed to their proposition and the first project was chosen: the 1934 novel Murder on the Orient Express, which was the original reason for the idea, having been suggested to Richard Goodwin by his daughter. It was also one of the few novels by Agatha Christie which had not yet been adapted into a movie.

To secure the financing of the ambitious project, Richard Goodwin and John Brabourne went to Nat Cohen, who had just taken the command of EMI Films and was looking for a prestige project. Murder on the Orient Express arrived at the right time, but Cohen only wanted to supply half of the budget, forcing the producers to look in the USA for another partner. They found their backing at Paramount Pictures, where they talked to Charles Bluhdorn, the owner of the parent company Gulf+Western. Being an Austrian in exile, he had seen the real Orient-Express during his childhood in Vienna and was now thrilled about making a movie with the famous train in it.

For the difficult task of transforming the novel into a film script the filmmakers had enlisted the help of British author Paul Dehn, who in the 1960s had not only written the James-Bond-movie Goldfinger, but with The Spy Who Came In From The Cold and The Deadly Affair two adaptations of spy thrillers by John LeCarré - on the latter he had already collaborated with director Sidney Lumet. It was Dehn's last movie - he unfortunately died only two years after the Premiere of Murder on the Orient Express, but he could not have wished for a better way to end his Hollywood career.

Paul Dehn proved to have an especially good sense for Agatha Christie's dialogues, who had not only written many novels but also a few plays and therefore had used a lot of talk in all her works. Murder on the Orient Express is no exception and maybe because of this the extremely dialogue-heavy story had not yet been adapted into a movie. Paul Dehn's script stuck close to the original, but some changes were necessary, because Poirots written account of his investigation had to be integrated into the plot of the movie. An intro was also added, which dramatised the history of the case in a somewhat unnecessary way, because it was also explained during the big finale.

From the beginning Sidney Lumet did not intend to stage the movie as a small chamber play, but deliberately as a large, glamorous big-screen epic with an all-star cast. In the 1970s it was still possible to accommodate many famous actors together in a movie without blowing up the budget - but even so the filmmakers had to use a trick. They first engaged Sean Connery, who had turned his back on James Bond in 1971 for the first time and had starred in only three movies so far. He was still waiting for a big chance to cast off his image as a secret agent and although his role in Agatha Christie's story was only one of many, it gave Connery a great opportunity to establish himself as a character actor.

With Sean Connery as a lure Sidney Lumet, Richard Goodwin and John Brabourne began to search for actors not only in England, but also in the USA and were overwhelmed with responses. The prospect of appearing in the first author-approved adaptation of an Agatha Christie novel since a long time was a great temptation which many could not resist. Because of this the cast list of Murder on the Orient Express looks like a veritable who-is-who of European and American actors, some of who were successfully recruited from retirement by the filmmakers.

Lauren Bacall, Ingrid Bergman, Jacqueline Bisset, Jean-Pierre Cassel, Sean Connery, John Gielgud, Wendy Hiller, Anthony Perkins, Dennis Quilley, Vanessa Redgrave, Rachel Roberts, and Michael York played the twelve suspects, Richard Widmark the victim of the crime and Martin Balsam and George Coulouris the director of the train company and the Greek doctor. This unique mix of experienced theater- and film-actors succeeded in giving each character something very special.

The casting of the leading role was not so easily accomplished, because there was already a very precise vision of Hercule Poirot - perhaps more precise than that of Agatha Christie's other protagonist Miss Marple. Sidney Lumets favoured actor Alec Guinnes was unfortunately not available and the only one who the filmmakers thought could play the difficult role was British actor Albert Finney. He launched himself with great enthusiasm into the character, but there was a big problem: he was only in his mid-thirties and actually much too young for the master detective.

But with the help of an elaborate makeup Albert Finney was transformed into a barely recognizable Hercule Poirot, although it was a huge encumbrance for the actor because it took a long time to get it done properly. In return it allowed him to play a stunning and original interpretation of his character. While the many supporting actors were certainly the big attraction of the movie, they were simply outacted by Albert Finneys unique performance. With an outrageous, but not entirely false franco-belgian accent the actor brought Hercule Poirot to life like no one had ever done before. It was unfortunately the first and last time he played the role - four years later the producers asked him to reprise his character, but he declined because of the exhausting makeup process.

Sidney Lumet focused on the experience of a train journey with the Orient Express, where the main part of the plot happens in the cramped premises of the train coaches. To make the illusion perfect, the departure of the train was shot in a long and complicated sequence in an abandoned railway workshop in Paris, introducing both the characters and the special atmosphere of the Orient Express. For this scene and the few location shots the original train could not be used, because it didn't exist in its entirety anymore - instead a similar-looking train assembled out of other historic wagons was used.

The Orient Express of the movie had the official name Simplon-Orient-Express and traveled in 1919-1939 and 1945-1962 from Istanbul via Sofia, Belgrade, Venice, Milano, over the Simplon-pass to Lausanne, Paris, Calais and via ship to London. Ironically it wasn't the same train, which Paramount-CEO Charles Bluhdorn had seen during his youth in Vienna - this actually was the Arlberg-Orient-Express, which ran at the same period via a more northern route from Bucharest via Vienna, Innsbruck, Zurich to Paris and Calais.

The location shots were filmed in the french alps with an especially assembled historical train, matching the real Simplon-Orient-Express on the outside, but not on the inside. The interior shooting was done in the british Elstree-Studios, where in big halls two complete train coaches were put. They were not completely genuine, but furnished by production designer Tony Walton after the famous originals down to the last detail. The scale of the coaches was not enlarged as usual to make room for the camera and the technical equipment, but left in the original cramped and claustrophobic state of the real Orient-Express.

The wonderful images were captured by cinematographer Geoffrey Unsworth, one of the best cameramen of the British film industry. He managed to find the most astonishing camera angels in the narrow corridors of the train coaches and filmed the departure of the train in a single, long, complicated scene. For the interior shots of the moving train no bluescreen technique was used but a complex back projection system. Bcause the main part of the plot happens when the train is standing these scenes are not frequently seen, but nevertheless they look deceptively real and help to create the special mood of the train journey.

For the music Stephen Sondheim had recommended the composer Richard Rodney Bennett to the filmmakers, who went an unusual way and in spite of the serious and mysterious atmosphere wrote an often merry and playful score. The main theme debuts during the credits as a majestic overture for piano and orchestra, while the departure is being accompanied by a second melody, which was composed as a swinging waltz to symbolize the rhythmic movement of the train. A couple of other pieces were added to the two main themes, which were mainly responsible to create the right mood for some scenes.

The composer had however refrained from giving each character its own melody, which would have been very complicated. Instead a large part of the dialogue-heavy scenes had no musical backing, while the score was mainly used for short interludes and as an accompaniment for the more dramatic parts of the plot. The music was recorded by the orchestra of the Royal Opera House of the London Covent Garden, which was conducted by Marcus Dods - Richard Rodney Bennett didn't have time for this, because he sat at the piano himself.

Agatha Christie had trusted the filmmakers fully and for the first time was really thrilled about an adaptation of her works - the usually very reclusive author even attended the British premiere of Murder on the Orient Express. In the USA the movie was at first only shown in two cinemas on the west and east coast, but the boxoffice results were so overwhelming that the film was quickly released all over the country. The movie was a big success all over Europe as well and managed to equally convince the audience and the critics. At the Academy Awards of 1975 Murder on the Orient Express was nominated for six Oscars, but due to the strong competition, amongst others Francis Ford Coppolas The Godfather II, only Ingrid Bergman won for her supporting role, which however stood for all the great acting achievements of the movie.

Three centuries after its making Sidney Lumets Murder on the Orient Express is still the crowning achievement of all Agatha Christie adaptations and is in its own right distinguished as a very special classic. Even John Brabourne's and Richard Goodwin's other three Christie-adaptations Death on the Nile, The Mirror Crack'd and Evil under the Sun were not completely able to achieve the brilliance of Murder on the Orient Express.

![]() The DVD

The DVD

Only a few years ago it looked like Murder on the Orient Express was as good as lost - the only country where the movie was available on DVD was Australia. The region 4 edition came from Universal, who licensed it from Studio Canal, who also owned the European rights. The Italian, French and Spanish DVDs were however only briefly sold, but in autumn 2002 all four Brabourne/Goodwin-Christie-Adaptions were released in England together in a box. Soon Kinowelt followed in Germany with Death on the Nile, The Mirror Crack'd and Evil under the Sun, but Murder on the Orient Express was delayed until Spring 2003.

While the other three movies had also been released in the USA by Anchor Bay, Murder on the Orient Express was a co-production with Paramount, who held the American homevideo rights. In late summer 2004 Paramount finally followed with a new DVD of the movie, which turned out to be the best version yet. The new transfer was a little better than on the previous discs and not completely perfect, but in return the American DVD boasted an amazing 5.1-soundtrack and a new documentary, which easily trumped the Kinowelt and Universal releases. If the German soundtrack is not needed, the Paramount-DVD should be the first choice.

![]() Image

Image

Nobody expected that Paramount would produce a completely new master for their DVD of Murder on the Orient Express, but as the American rights owner it seemed that the studio was not forced to use the material from Studio Canal, which had been used for all the previous European and Australian releases. As seen in the comparison Paramount had in fact made a new transfer, which made the difficult source material look better than on the old discs, but was still not completely perfect.

At first it should be said that Murder on the Orient Express was filmed "flat" in 1.85:1 - certain other reviewers claim that the movie was cropped from 2.35:1, but they were confused by a false entry in the IMDB. Paramount's new transfer shows a little more image information than the previous DVDs and has been opened up from 1.85:1 to 1.78:1.

The film source of this new transfer was in a much better condition than on the other DVDs, but unfortunately there was no thorough cleanup on the film material done, so that there are still some dropouts visible. This shows itself less in rough damages, but mostly as the occasional hair and other small dust particles, though they are most noticeable at the beginning of the movie and around the reel changes - reel change markers are fortunately not visible. There are no really serious damages, especially considering the movie has not been really restored. Nevertheless Paramount could have gone the additional step and do a further digital cleanup to remove the most obvious dropouts.

The new transfer can especially impress with an improved sharpness, which due to the generally soft look of the movie is not on the highest level, but makes the best of the source material. The better details are mainly the result of a very careful use of noise filters, which seem to have been used only very sparingly to remove the relatively heavy film grain. The grain is still constantly visible in a small, but completely normal amount and adds to a natural and lively look of the transfer while not being intrusive at all. The somewhat jumpy image of the older DVDs is still not completely steady, but has also been much improved in that respect.

A big difference is also the color timing, which improves the pale tones of the earlier DVDs a little bit, but still retains the deliberately pastel-like color palette. The blooming from white to dark image parts is still visible, but doesn’t look as heavy as before – it doesn’t seem to be a problem of the film source, but looks more like a well-used stylistic device.

Paramount has missed the mark for a perfect transfer of this wonderful film only by a small margin – if the film had been cleaned better, it could have been an excellent transfer. Even so the quality is on a comfortable level and Paramount's DVD of Murder on the Orient Express looks much better than the discs of the other studios.

![]() Sound

Sound

As average as the transfer is, the more exceptional is the soundtrack. In addition to a restored mono track Paramount has gone all the way by producing a fantastic 5.1-mix.

The 5.1-remix puts the emphasis on Richard Rodney Bennetts wonderful music. Paramount was able to remix the score from the original multitrack masters, so this is not a forced mono-upmix, but a completely discrete surround-mix, which sounds even better than on the soundtrack album. The music is spread to the edges of the frontal soundstage and even makes liberal use of the surround channels without using an unnatural echo. The quality is excellent and has perfect transparency and airiness, which can rarely be heard in film music of the 1970s.

The dialogue is conventionally confined to the middle channel and has the same clean and natural sound as on the mono-track. Although the voices have been nearly exclusively recorded on the set, they are perfectly understandable and can be heard crystal clear. In contrast the soundscape has been a bit extended and sometimes makes use of the rear speakers, but no sound effects have been re-recorded, so they don’t sound artificial at all.

The mono track has also been restored and seems to be a remainder from the remix. Its dialogues sound nearly similar to those of the 5.1-track, but the big difference is in the music. For a mono track the sound is quite impressive, but the enormously better music reproduction of the 5.1-version makes this soundtack somewhat redundant. For the sake of completeness it has its place on this DVD and the in comparison much worse-sounding French track reveals even more how great the English tracks really are.

Subtitles are only available in English language, however not only for the movie, but also for all the extras.

![]() Extras

Extras

In contrast to the European and Australian DVDs Paramount has treated the American release to some remarkable extras, which only at first glance seem to be a bit weak. The absence of an audio commentary may be regrettable, but it is doubtful that Sidney Lumet would have managed to talk about interesting things for more than two hours.

Making Murder on the Orient Express (48:32) by Laurent Bouzereau is a small, but nice documentary in three acts, which recounts the making of the movie in a very detailed way. Typical for a Bouzereau documentary there is no dramatic voiceover, instead extensive interviews with the filmmakers, actors and other involved are used and are only supplemented with a small amount of film clips and photographs. Not only director Sidney Lumet, but also producers John Brabourne, Richard Goodwin, composer Richard Rodney Bennett and the Actors Albert Finney, Sean Connery Jacqueline Bisset and Michael York have their say and are joined by Mathew Pritchard, Agatha Christie’s Grandson and Director and Writer Nicholas Meyer, who talks not as a participant, but as a fan and admirer. It is a very cheerful and friendly documentary which covers the filming and the preparations in many interesting details. The actors and filmmakers remember the movie with much enjoyment, some thoughtfulness and a healthy portion of pride of their joint project – they really appreciate to have participated in one of the best adaptations of a novel by Agatha Christie.

Agatha Christie: A Portrait (9:35) is an affectionate mini-biography of the writer by her grandson Mathew Prichard. He tells about the career of his grandmother from a very personal perspective, but doesn't get carried away with sentimentalities.

The Trailer (2:38) looks terribly scratched and is a completely different from the one on the Kinowelt and Universal editions – this American version from Parmount is much more heavy on the cheap thrills.