|

The Movie The Movie

Harry Palmer is just one small agent among many and not particularly enthusiastic about his job. When he is put on a boring but seemingly harmless routine assignment to investigate the disappearances of British scientists who later turn up brainwashed, he doesn’t have much hope of finding out a lot. But then he comes across an audio tape snippet with the mysterious inscription Ipcress – and soon events come to a head and Palmer no longer knows whom he can really trust…

When the first James Bond film was released in 1962, Len Deighton had published his first book The Ipcress File in the wake of the burgeoning spy craze, which quickly became a successful bestseller. The author, who originally worked in advertising as an illustrator and for some time had his own cooking comic strip in The Observer, was hailed by his critics as a new Ian Fleming whose tales were more realistic. Even Bond movie producers Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman took notice of the young writer and hired him as the first screenwriter for their new Fleming adaptation From Russia with Love, but they replaced him soon because he was not working fast enough and they didn’t like his style.

But Harry Saltzman had not forgotten Len Deighton’s unusual spy thriller with the nameless anti-hero and soon acquired the film rights to The Ipcress File and its sequels. A film adaptation was still some time away, as Saltzman, together with his partner Albert Broccoli, wanted to concentrate on the James Bond series first. After the great success of the first three movies, Saltzman saw an opportunity to bring an alternative to Ian Fleming’s secret agent into the cinemas- someone who was almost the opposite and represented a kind of spy that had never been seen before on the big or small screen.

Comparing Len Deighton’s agent with James Bond is obvious, but the two characters could not be more different: Bond is a secret agent with heart and soul and would let himself be torn to pieces for Queen and Country. Deighton’s nameless spy, who only acquired the name Harry Palmer for the movies, is just a lowly worker who is considered replaceable and superfluous by his superiors, never does his assignments completely voluntarily and certainly does not enjoy his work. He has no choice because he is being held responsible for some black market shenanigans during the war and his superior is actually not the secret service, but the war ministry.

Harry Palmer was not supposed to be a glorious spy, but just a disillusioned soldier who has to work off his sentence as an involuntary agent to escape worse. Nevertheless, he is no crook and has a sense of justice, but in the end all he cares about is how much he has in his bank account at the beginning of the month. After all, even a secret agent has to live somehow, especially if he has to beg his superiors for every little expense. Despite his small flat and modest private life, Palmer does have certain personal standards – his penchant for cooking, classical music and beautiful women are somewhat reminiscent of Johannes Mario Simmel’s Thomas Lieven, who is also one of the few involuntary agents in spy literature.

Originally, Harry Saltzman wanted to cast Christopher Plummer in the lead role, but the already established actor was not comfortable with a five film contract for an uncertain project and preferred to star with Julie Andrews in the musical The Sound of Music. Richard Harris also turned it down, so Saltzman had to look for other young actors and came across Michael Caine, who had been working in the theatre and in supporting roles in movies since the 1950s and was still waiting for his big break. After seeing him in his first big movie role in Zulu, Harry Saltzman signed Michael Caine and promised to make him a second James Bond – but in a completely different way.

Michael Caine proved to be the ideal choice for the laconic agent, whom he played in a very restrained, natural and somewhat satirical way and so came surprisingly close to Len Deighton’s book template. In addition, he was able to get his wish fulfilled to wear his glasses in the film so that he could simply take them off for other movies, not being trapped by his secret agent role. Short-sightedness and an everyman appearance were not the only trademarks of Harry Palmer, but also the dry and bitter cynicism of the novel, which Michael Caine knew how to bring perfectly to the screen despite his relatively restrained performance.

Michael Caine was supported by an excellent cast of actors who, just like him, were not big stars at the time. The biggest name in the cast list was British actor Nigel Green, playing Palmer’s new superior Major Dalby with a quintessential British military stiffness, making him not exactly one of the most likeable characters in the film. This was not the first time Nigel Green had appeared in front of the camera with Michael Caine, as the two actors had already appeared together a year earlier in Cy Coleman’s African war drama Zulu. The busy actor was able to demonstrate his skills brilliantly in The Ipcress File, making a memorable unsympathetic character out of Major Dalby.

For the role of Palmer’s old boss Colonel Ross, Harry Saltzman was able to recruit New Zealand actor Guy Doleman, whom he had previously hired for a small supporting role in the fourth Bond film Thunderball. His appearance in The Ipcress File is much larger, giving Doleman the opportunity to demonstrate a typically British bureaucrat, much like his co-star Nigel Green. Colonel Ross is by no means as unsympathetic as Major Dalby and, with his dry manner and his disparaging way of handling his subordinate Harry Palmer, is somewhat reminiscent of James Bond’s superior M.

Len Deighton had already included an unusual female supporting character in the novel, who also plays a small but important role in the film adaptation: Harry Palmer’s new colleague Jean, who is portrayed in the film very cool and mysterious by the relatively unknown actress Sue Lloyd. She has little to do with the glamorous girls of the James Bond films and even seems more like a strict Miss Moneypenny than a provocative spy playmate, but on the other hand she does not correspond at all to the usual stereotype and can also convince with intelligence and not only with her looks.

Harry Saltzman chose the young Canadian Sidney J. Furie as director, but soon wished he had found someone else: the producer was appalled by his seemingly chaotic working style. A fight quickly broke out between the tempestuous Saltzman and Furie, who at one time fled the production to escape from the producer’s tantrums and was only brought back by the persuasion of the crew and actors. Furie carried on despite the troubles and pushed through his unconventional methods, even if Harry Saltzman didn’t like it.

Together with veteran cameraman Otto Heller, Sidney J. Furie created an unusual visual style. The camera often showed the action from adventurous angles and the view of the wide Techniscope image is often obscured by objects, creating the unsettling impression of surreptitious observation. The unusual image composition seems strange at first glance, but works wonderfully as a narrative trick and gives the film a look all of its own, which was later often copied by many, but never used to such great effect as in The Ipcress File.

The screenplay adaptation by Bill Canavay and James Doran, two relatively unknown authors, naturally had to remove a lot from the very detailed and extensive novel. Only a few basic ideas were used, but the characters and the dark and pessimistic mood remained largely intact. A voiceover as an implementation of the first-person narrator was not employed because the vast amounts of text would have been too much for a film script and a running commentary would have destroyed the atmosphere of the film. This was compensated with an above-average amount of dialogue.

In contrast to the book, the plot takes place entirely in London, which was obviously a decision made mostly for economic reasons. Exciting parts of the book involving a nuclear weapons test were entirely removed, but this was was done in close cooperation with Len Deighton who contributed a few new ideas of his own. As a result, the implementation of the basic concept succeeded surprisingly well and was able to remain very faithful to the original story despite the massive deviations.

The plot remained complex and had little in common with other films of the genre, which were mostly constructed around action scenes. There are no big spectacles in The Ipcress File save for the explanation of the titular MacGuffin resulting in an uncomfortable torture scene, but nevertheless the plot has a surprising amount of story to offer. Lots of dialogue and very little classic action make The Ipcress File a downright intellectual film. Viewers who switch off their brain for even five minutes are liable to immediately lose the plot given the heavy density of the story. The Ipcress File is like a jigsaw puzzle – at the beginning the individual pieces hardly make any sense, only in the course of the movie their meaning slowly become apparent.

Instead of using lavish studio sets, The Ipcress File was mainly shot on original locations in London. It was, however, not the colourful swinging London of the sixties, but a grey, rainy big city that does not look particularly inviting. but is all the more authentic. The film’s setting is also a valuable contemporary document, showing a side of the British capital from the mid-1960s that is not often seen in movies of that time. Sidney J. Furie and cinematographer Otto Heller had achieved this by showing the city not from the exciting perspective of a tourist, but from the everyday view.

Ken Adam, who had previously made a name for himself with the gigantic sets of the Bond movies, was responsible for the production design and was Harry Saltzman’s first choice for The Ipcress File. His outlandish constructions were less in demand this time, as the task was to construct entirely ordinary looking sets. Although some scenes were staged at Pinewood Studios, the majority of the interior shots were filmed in a London apartment building converted into a studio, which doubled as a canteen, office and many other production departments. Ken Adam ensured that the sets were given a completely realistic look, which turned out to be a masterpiece precisely because of its unobtrusiveness.

In addition to editor Peter Hunt, producer Harry Saltzman had also borrowed another indispensable collaborator from the staff of the Bond films: composer John Barry, who had given the films his own very distinctive sound. For The Ipcress File, he remained largely true to his style, but showed his versatility by writing a very unusual theme music. Instead of a cracking title song, the opening credits are accompanied by a quiet, melancholic melody that excellently expresses the dark and mysterious mood of the film.

John Barry achieved the very special sound of his film score this time not only with his characteristic brass sections or an electrifying guitar solo, but mainly with the cimbalom, a dulcimer-like string instrument that is used more effectively in The Ipcress File than in any other film score. The title melody played on it is heard in many different arrangements, not all of which use the rare instrument as a solo voice, but which consistently employ an equally unusual rhythmic accompaniment of vibraphone, flute and only very sparingly used brass. With this unusual instrumentation, John Barry has created an impressively innovative film score.

The Ipcress File could have been a serious rival to the James Bond films, but the intelligent style of the movie with its extensive dialogue and complex plot was not really suitable for mass audiences. As a result, the big success failed to happen, but nevertheless The Ipcress File was able to win over quite a respectable regular audience and the critics were also consistently enthusiastic about the unusually sophisticated entertainment. In the End, Harry Palmer’s first adventure had two successors with Funeral in Berlin and The Billion Dollar Brain, which were not really big successes either, but count among the best spy movies of the sixties and today enjoy an excellent reputation as real classics.

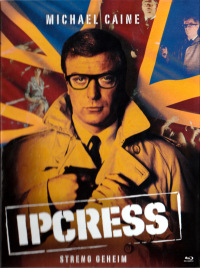

For Michael Caine, the film marked the start of a long acting career that continues to this day. Hardly anyone, however, can remember that today’s character actor once started out as the small-time secret agent Harry Palmer. The popularity of The Ipcress File, known in Germany by the relatively accurately translated title Ipcress – Streng Geheim, is limited and very much overshadowed by the competition, mainly of course the Bond franchise. But on the more realistic side of the genre, only John LeCarré and of course Len Deighton remain, whose The Ipcress File is one of the very best spy film adaptations.

The Disc

The Ipcress File had already been released on DVD by Anchor Bay in the USA in 1999, but unfortunately this disc has been out-of-print for a long time – this was a great pity, as it contained an excellent audio commentary with the late director Sidney J. Furie and editor Peter Hunt. In 2003 Koch Media released the film in Germany in very good quality, but without the commentary track. Fortunately the track surfaced again in a 2005 special-edition DVD release from Network in the UK that also contained quite a few new extras.

In 2014, the Network DVD release was upgraded with a new high-definition restoration for a Blu-Ray that had all the extras of the earlier version but a much improved transfer. It took a while for Koch to catch up, but in 2020 they finally delivered and released an expensive, but elegant special edition that not only contained all the British extras but also a third disc with Michael Caine’s My Generation documentary and a 17-page booklet inside a stylish Mediabook hardcover. Koch’s version of The Ipcress File is now simply the best one out there preserving the movie perfectly for the future. |

|

|

Extras Extras

Koch’s Blu-Ray release of The Ipcres File is not missing out and contains all the extras from the Network UK release and also adds a third disc with the 2017 Michael Caine documentary My Generation. The elegantly designed mediabook also includes a 17-page booklet with a German essay by Thorsten Hanisch.

Disc 1 (Blu-Ray)

The first disc has the Audio Commentary with director Sidney J. Furie and editor Peter Hunt, recorded in 1999 for the American Anchor Bay release. Peter Hunt passed away in 2002, so this commentary track is an important document and not a dull affair at all. Furie and Hunt are an extremely talkative duo and, while they can’t always remember everything, they take their own forgetfulness in good humour and still reveal quite a lot of anecdotes. The many problems of the film’s production also come up, and Sidney J. Furie talks openly about the trouble he had with Harry Saltzman. Despite a few small breaks, this commentary track is extremely lively entertaining.

The first disc also contains the Trailer (1:05) in HD and the original 2.35:1 letterboxed format, but it looks like it was upscaled from the DVD.

Trailers from Hell (1:20) is a short but concise introduction to the movie from the eponymous website by Howard Rodman, new to this Blu-Ray

The Radio Spots are the Original US Radio Commercials from the british release- Four radio commercials that have nostalgia value but are nothing really special.

The Textless Material (4:27) has been, like the main movie, re-scanned in high definition and consists of the film’s opening and closing credits – but without the text overlays and without sound. Intended strictly for the archive and international releases, it is nevertheless amazing that this has been included on this release too.

The Stills Gallery was also ported from the old DVD release, but remastered in HD and a slightly better format. With 123 large-format production photos and posters, this is surprisingly well stocked.

Disc 2 (DVD) has all the remaining extras from the 2005 Network release in Standard Definition.

Candid Cane (44:20) is an old London Weekend Television programme from 1969 that covers in detail the still very fresh career of Michael Caine, who is featured in an extensive interview.Although there is of course a high nostalgia factor involved, this particular type of documentary is an ideal complement to the other extras on the DVD and not just an embarrassing supplement dusted off from some oldarchive.

The Interview with Michael Caine (21:08) was newly produced for the 2005 Network release and is actually not a simple interview at all, but a small documentary in which Michael Caine tells many interesting stories about the making of the film and his role. Professionally edited with some short film clips and photos, this interview documentary has very high information content despite its short running time.

The Interview with Production Designer Ken Adam (10:30) is structured very similarly to the first interview and also gives more the impression of a mini-documentary. The featurette is actually only so short because Ken Adam (armed with his eternal cigar) quickly gets to the point and describes his work on The Ipcress File in an impressively concise manner.

The Ipcress File – Michael Caine goes Stella (4.57) is a short sketch with Phil Cornwell as a remarkably good Michael Caine impersonator, giving a brief but crisp introduction to The Ipcress File and his further career. Phil Cornwell could indeed be mistaken for a young Michael Caine, but after all, he has been perfecting this and many other roles in the English sitcom Stella Street for a long time.

Disc 3 (Blu-Ray)

My Generation (85:25) is the only extra occupying the third disc exclusive to the German release, a Blu-Ray containing Michael Caine’s own 2017 documentary about the 1960s. Actually written by comedy writers Dick Clement and Ian LaFrenais and directed by David Batty, it contains an abundance of archival footage and lots of interviews with many sixties icons from art, music and movies led by Michael Caine himself. Although only vaguely related to The Ipcress File, it’s a very nice extra that is not available separately.

|

|

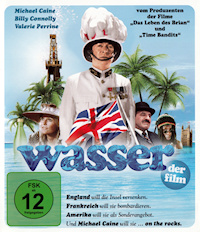

To my great surprise, one of my favourite movies was released on Blu-Ray last year: 1985’s Water, one of the great Handmade Films comedies! It previously came out almost 20 years ago on DVD, which was a big surprise too. The Blu-Ray is “only” sourced from the same old HD master, but that’s good enough for a movie that was previously almost lost in the battle for the Handmade rights.

To my great surprise, one of my favourite movies was released on Blu-Ray last year: 1985’s Water, one of the great Handmade Films comedies! It previously came out almost 20 years ago on DVD, which was a big surprise too. The Blu-Ray is “only” sourced from the same old HD master, but that’s good enough for a movie that was previously almost lost in the battle for the Handmade rights.